Issue 36 | April - June 2024 |

Our Purpose: To identify excellent Florida freshwater fishing opportunities and to provide anglers with relevant information that will enhance the quality of their outdoor experience. If you reached this newsletter through a website link instead of receiving it by email, you can subscribe free at the Subscription Topics page under "Freshwater Fishing". Having trouble viewing this email? View it as a Web page. |

In this issue:

|

TrophyCatch Tracker

Florida has many famous bass lakes, but river fishing produces giants too as James Shubert's 14 lbs. 8 oz. Withlacoochee River catch attests. TrophyCatch's peak annual quarter of fishing is producing some great catches, including the current Season 12 leader caught in the Withlacoochee River by James Shubert and weighing 14 lbs. 8 oz. (above). Nice fish from across the state continue to come in, and we hope your next catch might be among them. The current TrophyCatch numbers are below.

Register for TrophyCatch or view approved angler catches to help plan your next fishing trip at TrophyCatch.com. Follow TrophyCatch Facebook for featured big bass, program updates and partner highlights. For more news and freshwater information follow us on the FishReelFlorida Instagram.

Keep your eyes open for a pink tag (circled) on any bass from the Northwest Winter Haven Chain of Lakes, Lochloosa Lake, Lake Beauclair, Lake Okeechobee, or Porter Lake! Featured Fish: Yellow Bullhead

Fishing Techniques: Small Boats Part 2

Small boats provide big adventure! Florida's 8,000 named lakes and 12,000 miles of rivers offer almost unlimited exploration for go-anywhere small crafts. Last issue introduced the big advantage of small boats, including float tubes, inflatables, and kayaks. This issue wraps up with canoes and johnboats, and some general small boating advice.

Johnboats Johnboats just make our list of craft that can be car-topped and hand-launched. By our 70-pound limit, 12’ will be the maximum size. Ten-footers are also available but will usually be one-man craft due to their smaller weight capacity. Johnboats, in their historical form as wooden punts and skiffs, are also old-timers in the boating world. Modern models are exclusively aluminum. The flat hull makes the most spacious and stable fishing platform available in the “small boat” world. However, it also makes the johnboat strictly a calm-water craft; it doesn’t take choppy water well. Most johnboat users will drop a small electric motor or gas outboard on the transom; just pay attention to the rated horsepower as many smaller johnboats are very limited in what they can handle. If you plan to row, row, row your boat, do yourself a favor and get the oarlocks that clamp right onto the oars. Pop-off swivel seats and an anchor are other accessories to consider. Expect to pay between $450 and $600 for a 10’ to 12’ johnboat and note that the cheaper editions will often be made of lighter gauge aluminum and therefore be easier to carry. Photo: A johnboat is the classic Florida small craft. The last word Due to their reduced size, small watercraft are less stable than larger vessels. The FWC recommends always wearing a personal flotation device (PFD) on the water while in any vessel. Obviously, exercise common sense in which areas you access—don’t drop an inflatable into the busiest waters. And always watch for even moderately foul weather—small craft can’t handle it. Also, make sure you’re legally accessing the shoreline where you’re dropping in. Finally, small craft will take you places other anglers can’t go. So be polite to the homeowner not used to seeing someone off the end of their dock. Let them know how you got there if they ask, and tell them how much fun smaller watercraft can be. You might just find a “small boat” convert on your hands! Featured Site: Newnans Lake

Newnans Lake offers 5,800 acres of scenic fishing. Size: 5,800 acres Location: Alachua County Description: Newnans Lake is an FWC Fish Management Area located about two miles east of Gainesville on Highway 20. The lake is surrounded by cypress trees that provide good angling when water levels are high. Sparse areas of emergent grasses, bulrush, and spatterdock (water lilies) are found around the shoreline of Newnans Lake. The bulrush was planted by FWC in the late 1990s and early 2000s in order to enhance habitat. Excellent black crappie fishing is often the talk of the town, with Newnans Lake often being the top destination in the area for anglers looking to catch their limit. Largemouth bass are not quite as popular in Newnans, but there are some locals who know that quality bass fishing can be found on the lake if conditions are right. The most consistent fisheries on Newnans Lake are catfish and bream, and these can be caught year-round in deeper areas of the lake and the lake shoreline, respectively. There are some water quality challenges facing Newnans, primarily shallow, turbid water that limits light penetration and prevents the establishment of submersed aquatic vegetation and limits emergent plant growth. The result is that complex habitat is largely limited to the shoreline, with the exception being a large area of spatterdock offshore on the north end.

Fisheries Biology: How Fish Swim

"He swims like a fish!" It's an expression you might have heard at the beach or during a swim meet. But how, exactly, do fish swim? Water is a much denser substance than air, and therefore much more difficult to move through. Fish must be hydrodynamically streamlined (think "aerodynamically," only underwater) in order to travel efficiently. For some species, speed is most important, while for others, maneuverability and turning ability are critical. In fact, you can tell a lot about how a fish moves—and how it makes a living—simply by the shape of its body. First, how do fish swim at all? Basically, they undulate their bodies through the water in a snakelike motion. The undulations pass through the fish’s muscles in waves, and end with a brisk tail snap.

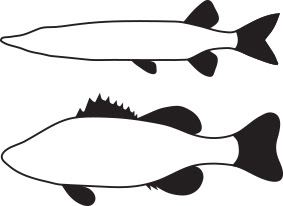

Fish swim by undulating through the water. Forward motion is provided by both the pushing of the fish’s body against the water, and by the final tail snap. The water is actually pushed backward and—in accordance with Newton’s Third Law that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction—the fish itself is thrust forward as this water is pushed off the fish’s body and tail. The rate at which these undulations pass through a fish’s muscles have a direct relationship to a fish’s speed. In some ways, this thrust is similar to that produced by the propeller on a boat motor. A long, skinny fish such as a pickerel derives most of its forward motion from the muscle wave. Part of this is due to the fact that such a long fish can generate more waves in its body than a stubbier and thicker fish. Also note that a pickerel’s fins have a relatively small surface area compared with the length of the body, and the small caudal (tail) fin provides a correspondingly smaller amount of forward motion during the tail snap. On the other hand, a stockier species like the largemouth bass gets most of its speed from the tail snap of its large caudal fin, but not as much forward thrust from the muscle wave of its stubbier body. As the illustration below shows, a bass can’t generate as many waves in its shorter and stiffer body as a long supple pickerel can. For nearly all fish, though, both are important in providing thrust.

A long, supple pickerel (top) can produce more muscle waves along its body than a short, stocky bass (bottom). What can we learn about how a fish lives by how it swims? Once again, let’s compare the pickerel and the bass. The pickerel’s long streamlined body is designed for speed. Its small fins tend to be farther back on its body, increasing its hydrodynamic efficiency and allowing it to “knife” through the water more easily. The pickerel can therefore be assumed to be a high-speed feeder, able to run down and capture its prey. You can also assume that if this is true, then the pickerel must feed on fast-moving prey organisms such as fish as opposed to slower foods such as crayfish. And this is exactly the case. The largemouth bass, on the other hand, is stockier in build and probably only able to achieve high speeds briefly and over short distances. Thus, a largemouth is an ambush feeder, surprising and capturing its prey from a relatively short range. The comparatively larger size of its fins, as well as their placement closer to the center of the body, also indicate that for a bass, maneuverability is more important than velocity. Rather than running down prey over distance, the bass should be able to turn and maneuver sharply enough to capture its food almost immediately once it gets close to it. In addition, rather than concentrating its diet strictly on fast-moving prey, the bass is more likely to be a generalist predator, eating a broader range of prey species than the pickerel (able to capture fish when the opportunity arises, but also consuming such prey as crayfish and frogs). Again, this proves to be the case.

Note the differences in body shape and size, and the position of the fins between a pickerel and a bass. How fast can fish swim? As one can imagine, clocking fish underwater is not easy! However, bass have been measured traveling at about 12 miles per hour (mph), and salmon slightly faster at 14 mph. The real speed records, however, go to saltwater fish. The barracuda—very similar in shape and feeding strategy to the pickerel—can move at about 28 mph. By far the fastest fish are the open ocean species. Bonitos and marlin have been estimated to reach 40 mph, while speeds of up to 60 mph (!) have been attributed to swordfish and tunas. To contact the Florida Freshwater Angler, email John Cimbaro. Fish illustrations by Duane Raver, Jr. and Diane Rome Peebles. Bass photo by Glen Lau. |

No comments:

Post a Comment